The Singapore Architecture Collection’s historian, Dr Wong Yunn Chii, who is supporting the collection’s efforts, shares why archival materials from the architectural and urban design practice are critical to understanding our past and charting our future. An Honorary Fellow at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore (NUS), Dr Wong has been quietly collecting architectural archival materials for over two decades.

5-minute-read

One of his first discoveries began with a call from a former colleague and architect who was spring cleaning materials for an office move. Upon arrival, he was greeted by a line of black garbage bags along the corridor.

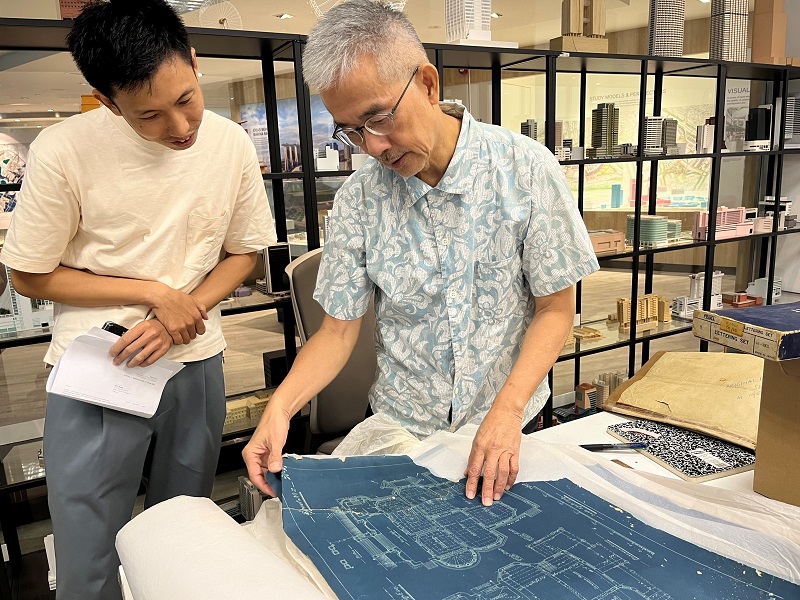

Dr Wong Yunn Chii at the interview with writer, Justin Zhuang.

“I opened these bags, and lo and behold, there were tonnes and tonnes of pamphlets. That got me excited!” he recalls of the visit during the mid-2000s.

The “garbage” included over 600 property brochures dating as far back as the 1960s, with those of Golden Mile Complex, Lucky Plaza, as well as Colombo Court and Pearl Bank Apartments. It was there and then that the architecture historian realised that he has stumbled upon treasures and proceeded to lug them home for safe storage.

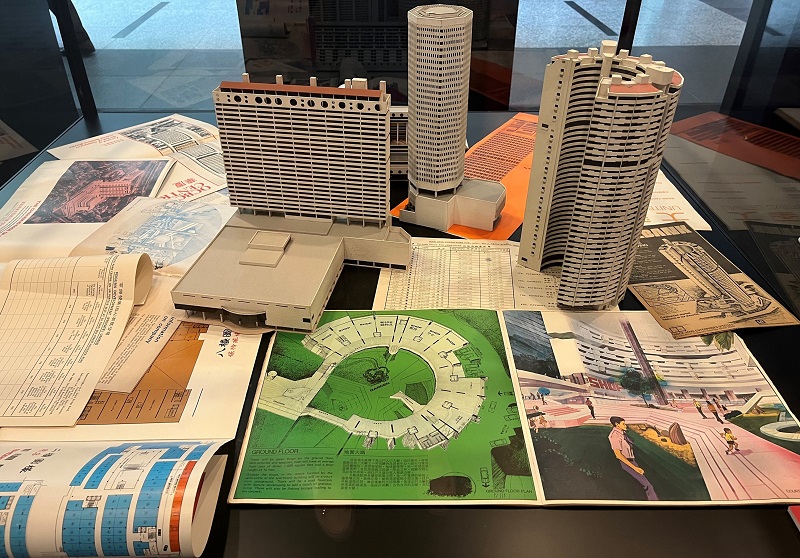

Examples of sales brochures in Dr Wong’s private collection. Credit for these brochures: Dr Wong Yunn Chii.

This was the first of several “rescue” calls Dr Wong has responded to over the last two decades, allowing him to amass hundreds of artefacts related to Singapore architecture. Besides sales brochures, he received building models, drawings, architecture books and even professional tools such as airbushes that have long become obsolete.

The idea to start collecting architectural artefacts then came to Dr Wong when he was teaching at NUS. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of its School of Architecture in 1998, he co-curated an exhibition of the department’s history with his then colleague, Dr Lai Chee Kien.

They interviewed the alumni about their school experiences and tracked down their works, including theses and portfolios. After the project, Dr Wong, better known as “YC”, became the go-to-guy for architects who wanted to give away their old stuff from their offices.

Visualising aspirations and lifestyles

“Generally, architects see these drawings and documents they create as part of their bread-and-butter work. They create them because the clients require them to be produced. As a historian, they hold many things to me,” he says. “I’ve always had an interest in all things old because they reveal interesting facets of our past.”

Consider the illustration in the sales brochure for Futura, one of Singapore’s first condominiums, which showcased its apartments with images of interiors furnished with space-age furniture, campy art and inhabited by owners dressed in bell bottoms and suits with huge collars. It captured the lifestyle and tastes during the 1970s when the property was first launched, says Dr Wong.

A page from the Futura sales brochure that reflected people’s tastes and lifestyles in the 1970s. Image credit of the brochure: Wong Yunn Chii.

“It’s not just a drawing. It’s a translation of popular imagination and desires,” he adds. “These brochures are a hotbed of visual materials for cultural historians, and anyone interested to know our past.”

Reflecting architects’ minds and imaginations

While colourful marketing ephemera may be the most captivating items in his collection, what interests Dr Wong more are the drawings by architects.

These include initial sketches and conceptual drawings that architects produce when developing a design and presenting ideas to clients, as well as submission drawings that are sent to the regulatory authorities to approve the final building design.

“A drawing by an architect or an urban designer is very honoured in the architectural and urban design tradition because it is seen as a trace of the mind,” he explains. Through such in-progress drawings and iterations, we get to understand how the final designs of buildings we experience today were initially conceptualised. We get to also infer and appreciate the different perspectives, scenarios and contexts the architect considered in his designs before finalising them.

Drawing upon past challenges and solutions

Architectural archival materials can also offer insight into how architects navigated challenges such as site constraints, technical issues, client demands, and the building policies of the day.

“We have words to describe, but we don’t have things to see. Seeing the architectural drawings and other visual materials not only fill in our knowledge gaps but enable us to infer for ourselves what was it that the architects were thinking of and interested in as they drew and described things,” he says.

For instance, Dr Wong has several sketch books of early local architects studying how buildings interacted with light. The drawings suggest to him that many in the profession were very interested in the quality of building surfaces, probably because there was a limited palette of materials to work with in the past.

Dr Wong Yunn Chii showing the writer, Justin Zhuang, an example of an architectural drawing from his private collection.

“From these drawings, you sense a delight with imagining how buildings might look like in light, appreciating its materiality, texture and the fine details,” he says. Such is the level of detail and study that is required of the craft, and therein lies a treasure trove of insights for future architects and designers.

Heirlooms for future generations

As a historian supporting the Singapore Architecture Collection efforts, Dr Wong hopes to raise awareness of the architectural and urban design profession’s craft and techniques, and ultimately inspire current and future practitioners to continue improving the quality of our physical environments and on people’s lives. His own private collection of architectural archival materials is also being considered for contribution to the Singapore Architecture Collection.

Examples of the sales brochures and other materials from Dr Wong’s private collection, on the Golden Mile Complex and Pearl Bank Apartments.

“For me, collecting and preserving architectural archival materials is like saving an heirloom that you can pass on. Later generations may view the materials and observe that a particular period of work may be more primitive, but nonetheless It reinforces the idea that we are continuously progressing and improving,” Dr Wong says, as he points to the surviving architectural drawings of cattle sheds as one of the few signs of this city’s rural past.

Dr Wong sharing about Singapore’s architecture with students from the National University of Singapore.

“If we do not have any photographs or drawings of such buildings, you can’t even begin to visualise. The collection is intended to raise awareness of how things have changed and why they have changed,” he adds.

About the Singapore Architecture Collection

The Singapore Architecture Collection reflects deeper efforts to document and preserve archival materials about Singapore’s modern and contemporary architecture. These records tell the stories behind the design of our landmarks and everyday places and inspire present and future generations in shaping Singapore’s built environment. Architects, planners, urban designers and other members of the built environment industry are invited to contribute their materials to help enhance and enrich the collection.

Learn more about the collection here: https://go.gov.sg/sgarchitecturecollection.For queries or to donate to the collection, write to enquiry@nlb.gov.sg.