Architectural photographer, Darren Soh, shares his love and passion for photographing Singapore’s architecture, reinforcing the importance of the Singapore Architecture Collection in helping us to appreciate the many interesting buildings and housing blocks that make up our cityscape and home.

Image: C.Y. Kong.

3-minute-read

How did you get started on photographing Singapore’s architecture?

Darren: I started off photographing weddings, events, and portraits but it was only in 2006 that I began photographing buildings after I bought a large format camera to experiment with.

Big Splash (1977-2006), designed by Timothy Seow & Partners, photographed with a large format camera in 2006. Image: Darren Soh.

My interest in the craft gained further momentum after magazines such as Wallpaper* and Monocle commissioned me to shoot Singapore’s architecture in those earlier years. In the beginning, I focused on making the buildings look attractive but over time, I got more curious about the intricate details and stories behind the buildings that I photograph and started researching more on my own accord.

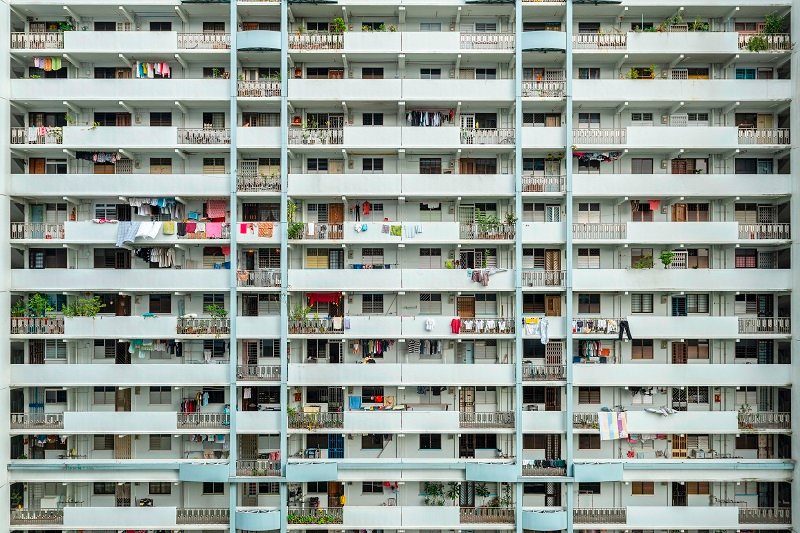

In the last decade, you have photographed many public housing blocks and shared these on your social media channels regularly. Why have you done so?

Darren: We have one of the best public housing programmes in the world and yet we do not have many visuals to show this. One of the first public housing blocks I photographed was Block 82 Commonwealth Close. Coincidentally, this was the area where I grew up in and was where the first flats were sold to the public in 1964.

Blk 82 Commonwealth Close. Image: Darren Soh.

If you observe closely, our housing blocks feature a wide variety of designs stretching back from the 1980s when the Housing & Development Board (HDB) consciously created differentiated designs to embrace and accentuate the elements and character of our local neighbourhoods.

It’s amazing how housing architecture can also foster a greater sense of home and rootedness.

Beyond the iconic buildings, you also shoot lesser-known ones.

Darren: A lot of my personal work focuses on buildings that are not iconic but are equally important. It’s something I find worth doing because our built environment is made up of many interesting buildings that have stories to tell.

An example is the New Bridge Centre, a commercial complex conceived in the 1970s and built in the 1980s. It was HDB’s first attempt to do something inspired by the surrounding area of Chinatown.

New Bridge Centre. Image: Darren Soh.

It was deliberately designed to look like a huge shophouse, with two double height pitched roofs and one taller than the other. Its roof even uses similar terracotta material. When it was first completed, the unusual design caught the attention of many and was even featured in the newspapers.

Another unusual building is AMK AutoPoint, a five-storey industrial building in Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park. It was built in the 1990s to relocate ground-level auto workshops in Sin Ming. Its design by CESMA International, then a company wholly owned by the HDB, is reflected as a structural design that also supports elements such as the car ramps.

AMK AutoPoint. Image: Darren Soh.

This architectural style was called structural expressionism, which was popular in other countries then and can be found in buildings such as Lloyd’s bank in London and the Centre Pompidou Museum in Paris.

What are some buildings that you regret not photographing?

Darren: The National Theatre, but I was too young. It was demolished in 1986 when I was in Secondary School. Many Singaporeans from that generation, including myself, would have stood in front of its half-moon fountain and had a photograph taken.

Another building is the former pagoda columbarium in Mount Vernon. The design by the Public Works Department combines a modernist structure with an ethnic Chinese roof. It’s an interesting choice for a Chinese columbarium and an example of how government agencies then were into this very literal way of using architecture to reflect specific identities.

How has photographing architecture in Singapore helped you to better appreciate the city?

Darren: It has helped me understand our buildings even more, in finding out why things are the way they are. For instance, Bishan Central has all these buildings with squares and triangles designed on them as it was a way for the architect to create a distinct estate using shapes and forms. So, there is a reason behind every design.

501 Bishan Street 11, with its design that has squares and triangles. Image: Darren Soh.

There are many other mysteries behind our building designs that I would like to uncover. For example, in Redhill Close, there is a multistorey carpark with a spiral staircase next to it that looks like a turret and even has a pointed conical roof. I’m curious why it was designed this way!

Multistorey carpark at 88 Redhill Close showing the spiral staircase with a conical roof. Image: Darren Soh.

I’m also very interested in understanding the origins of how our architects and designers got started. Through my work, I’ve learnt how some well-known local architects today once worked in the HDB. It’s interesting to find out where architects started and how their practice has evolved.

What are you looking forward to seeing in the Singapore Architecture Collection?

Darren: Beyond architects and designers, I hope the collection can help spotlight engineers, builders and others who help to realise and build our architecture.

Singapore Airlines Hangar, designed by architect Raymond Woo, photographed with a large format camera in 2006. Image: Darren Soh.

By sharing collection materials and about Singapore’s architecture through curated exhibitions, talks and photo walks, people can also learn more about how our buildings came about.

We all have short memories; this is why we need a collection like this to remind us of how valuable Singapore’s architecture is to us.

About the Singapore Architecture Collection

The Singapore Architecture Collection reflects deeper efforts to document and preserve archival materials about Singapore’s modern and contemporary architecture. These records not only tell the stories behind the design of our landmarks and everyday places, they can also inspire present and future generations in shaping Singapore’s built environment. Architects, planners, urban designers and other members of the built environment industry are invited to contribute their materials to help enhance and enrich the collection.

For more information about the collection, go to https://go.gov.sg/sgarchitecturecollection. For queries or to donate to the collection, write to enquiry@nlb.gov.sg.

Source: https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Resources/Ideas-and-Trends/Appreciating-Singapore-architecture-through-new-lens